As soon as 24-year-old Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published The Sorrows of Young Werther in 1774, it became an instant best-seller. The epistolary novel about a sensitive young man who takes his own life as a result of a love triangle led to a Werther Fever of young men dressed in blue jackets and yellow vests who honored their hero through musical compositions, paintings and decorative art objects.

One avid reader of this emotional Sturm und Drang work was Carl August, Duke of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach. In 1775, the duke invited the sudden celebrity to join his court in Weimar, Germany. The opportunity would prove to be a beneficial one. “Where else can you find so much that is good in a place that is so small?,” Goethe later reflected about Weimar.

Goethe moved into a little garden house, covered with Frankfurt roses, that was situated in the city’s Park an der Ilm. Designed to recall a romantic English landscape, the park includes a Classical Roman house built for Duke Carl August, Gothic ruins, an underground space in which to store beer, and even a patch of land that Goethe designed. The attention-getting young man became the talk of Weimar, as he introduced people to ice-skating on the Ilm River, told stories, made up poems and read from his works.

In 1782, Goethe left his Gartenhaus, moved to a Baroque house on Weimar’s Frauenplan, and stayed there for almost 50 years until his death in 1832. Here, the celebrated writer and statesman explored his diverse interests, including biology, physics, mineralogy, botany, astronomy and art.

During World War II, Goethe’s possessions in the house were removed for safekeeping. The building was seriously damaged by bombing in 1945, but was restored and is open for tours.

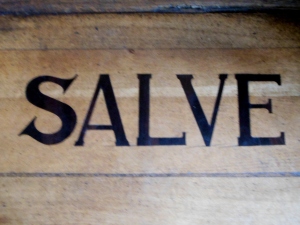

Goethe extended a standing invitation for people to gather in his home every day, even when he wasn’t home. His guests could stay as long as they liked, playing cards, making music, giving readings, and talking. He designed a staircase with shallow steps, like those he admired from ancient Greece and Rome; ascend it and come upon the greeting he chose to welcome his guests.

In 1777, Goethe journeyed to the Harz Mountains and ascended the Brocken, the highest peak in the range, an event so significant that he immortalized it in his poem, “Winter Journey in the Harz.” During his descent, he saw a spectacular display of colors, which he recalled in his Theory of Color, which he wrote in 1810. “…If during the day pale violet shadows had already been noticeable against the yellowish tone of the snow, one would now have to call them deep blue, as an intensified yellow was reflected from the sunlit areas. When the sun at last began to set, however, and its beams, very much moderated by the stronger mists, bathed the entire surroundings with the most beautiful purple color, the color of the shadows was transformed into a green which, in its clarity could be compared to a sea green, in its beauty to an emerald green. The spectacle grew more and more vivid. I felt I was in fairyland.”

Goethe was so fascinated by colors that he developed a theory based on how colors and color combinations affect the human mood. He recommended ways color could be practically applied, from the color of clothes to be worn on particular occasions to the color that various rooms should have. For example, Goethe received his visitors in the Yellow Room, in which he intended to create a cheerful, lively atmosphere. The Festive Hall was painted bluish-grey, making it elegant and uplifting. His study and bedroom were painted a calming green.

The main rooms in the front of the house were official spaces that Goethe used for meetings and receptions. For example, concerts took place in Juno’s Room, so named for an immense plaster cast of a 4th century B.C.E. marble bust which Goethe placed there in 1828. Goethe’s private rooms are at the back of the house. His study — where he wrote much of his poetry, autobiographical work and treatises related to art and science — is furnished just as he left it. Simple, functional furniture, a cushion on the table on which he rested his arm when he read for a long period of time, and no pictures on the walls — just instructions to his gardener tacked to the window frame — express his workstyle. Many of these objects are captured in an 1831 oil painting of Goethe in his study with Johann August Friedrich John, his secretary, which has hung in Weimar’s Anna Amalia Library since 1840. Beside the study is the library, which includes more than 5,000 books, and a room filled with showcases that display the minerals he collected and classified. In Goethe’s bedroom, you can see the pine chair on which he was sitting when he died.

Goethe’s private rooms are at the back of the house. His study — where he wrote much of his poetry, autobiographical work and treatises related to art and science — is furnished just as he left it. Simple, functional furniture, a cushion on the table on which he rested his arm when he read for a long period of time, and no pictures on the walls — just instructions to his gardener tacked to the window frame — express his workstyle. Many of these objects are captured in an 1831 oil painting of Goethe in his study with Johann August Friedrich John, his secretary, which has hung in Weimar’s Anna Amalia Library since 1840. Beside the study is the library, which includes more than 5,000 books, and a room filled with showcases that display the minerals he collected and classified. In Goethe’s bedroom, you can see the pine chair on which he was sitting when he died.

Goethe’s home was a showplace for his collections, which he precisely arranged and displayed. Plaster casts of ancient sculptures, drawings from Pompeiian frescoes, Gothic stained glass, copies of works by Raphael and Titian, Italian majolica and landscape sketches by English artists are some examples of his varied collecting interests. Specially designed cabinet drawers contain the thousands of drawings that he organized and cataloged.

Next door to the Goethe House, the Goethe National Museum features a seven-room exhibition that explains Goethe’s life and work through objects like his “Carrick” wool and velvet travel coat from 1815.

Goethe’s fans who make the pilgrimage to Weimar also track down the oldest surviving ginkgo tree in the city, planted across from the Anna Amalia Library in 1820. The ginkgo tree was a prized possession in the English-inspired landscapes that were so popular during Goethe’s day.

Goethe was so taken by the tree and the shape of its leaf that it inspired his poem, Ginkgo Biloba, which he published in 1819.

Continue your Goethe pilgrimage with a visit to Auerbachs Keller in Leipzig, one of the best-known restaurants in the world since its establishment in the 16th century. Goethe incorporated Auerbachs Keller in his most famous work, Faust. The restaurant includes rooms adorned with representations of the German legend in which a dissatisfied scholar makes a pact with the Devil, exchanging his soul for knowledge and worldly pleasures. This depiction of Faust and the Devil was carved from a single tree trunk.

For more on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, read Goethe: Life as a Work of Art, by Rüdiger Safranski. For enlightening information about an early patron of the Goethe Museum and Goethe’s role in a very different picture of Weimar culture, see “Goethe’s Oak,” a chapter in The Book Thieves: The Nazi Looking of Europe’s Libraries and the Race to Return a Literary Inheritance, by Anders Rydell.